God Clearly Does Choose

“For many are called, but few are chosen.” — Jesus in Matthew 22:14 (cf. Acts 13:48,2:23; Mt 22:14; Eph 1:4,11; Jn 15:16,18-19; Jn 6:44,65; Ro 8:29-30; 9:11-16; 1Pe 1:2; 2 Pe 1:10; Re 13:8,17:8; Lk 24:45+1Cor 2:14; Jn 17:9, and Ro 10:9+1Cor 12:3+Lk 6:46)

Contents

- 🤖 Hard-Determinism & Fatalism

- ⛓️ Soft-Determinism

- 🤖 Indeterminism & Libertarianism

- ⚖️ Theological Compatibilism

- ⚖️ Conclusion

- 5.1 On Proginōskō

- 5.2 Men as Responsible

- 5.3 God as Sovereign

- 5.4 Free Will Test

- 5.5 Final Thoughts

Many of you might start to ponder the thought-provoking question of how free our wills actually are. None of us had any free will or agency over where we’d be born, our ethnicity, our socioeconomic status, who our relatives would be, what genetic predispositions and genetic disorders we may be vulnerable to, or genetic physical traits such as height, eye color, intelligence, and natural aptitudes. We certainly don’t have any control over purely random actions, chance, or catastrophic events. Can you save yourself by reciting a works-based sinner's prayer or declare yourself justified before God through your own free will choices? **Do you believe that you have the free will to renounce your faith and forfeit salvation?** (See Free Will Test). If you answered "no" to these questions, the good news is you're still sane. Nevertheless, we do exercise a limited form of free will in our decision-making processes. Dr. Walter Martin (2017), a theologian with 5 degrees, articulates the limitations of free will:

… and that no flesh should be able to glory in its own sight, but whoever makes an appearance before the throne of the Lord, his glory will be in the Lord of hosts. Now some may say, “That’s the sovereignty of God, hallelujah, but what about my free will?” Well, it’s not as free as you think it is. You are free to make choices, but you are not free to enforce all of them. … There is freedom, but it’s quite limited. In lots of respects, “you have not chosen me; I’ve chosen you” means that God has the last word” (20:25).

I would submit to you that any intelligent examination of scripture leads to a belief in the doctrine of election. When I contend that a rigorous and scholarly examination of biblical texts leads to a substantiated belief in the doctrine of election, I am delineating a critical distinction: Belief in election to life does not necessarily entail an acceptance of foreordained damnation. In fact, it does not even require one to subscribe to the concept of foreordination in any form. Rather, election to life can be understood in a singular, prescient context, emphasizing a divine awareness of foreknown relationship rather than foreordination.

“Free will carried many a soul to hell, but never a soul to heaven” (Spurgeon).

I. 🤖 Determinism & Fatalism

- 🟡 “It is a matter for metaphysical decision which of these alternatives is to be chosen, a point made clearly enough by the existence of both an indeterministic interpretation (Niels Bohr) and a deterministic interpretation (David Bohm) of quantum theory, each having the same empirical adequacy in relation to experimental results, so that physics by itself cannot settle the issue between them” (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. xi).1

Many of history’s most brilliant thinkers, including Newton, Leibniz, and Einstein, subscribed to the philosophy of determinism. This view holds that all events, including human actions, are determined by preceding events in accordance with the laws of nature. Free will is an illusion, and thus, moral responsibility is also negated. However, this understanding was fundamentally shaken by the advent of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle.

Newtonian Determinism says that the universe is a clock, a gigantic clock that’s wound up in the beginning of time and has been ticking ever since according to Newton’s laws of motion. So what you’re going to eat 10 years from now on January 1st has already been fixed. It’s already known using Newton’s laws of motion. Einstein believed in that. Einstein was a determinist.

Does that mean that a murderer, this horrible mass murderer isn’t really guilty of his works because he was already preordained billions of years ago? Einstein said well yeah, in some sense that’s true that even mass murderers were predetermined, but he said, they should still be placed in jail … (Kaku, 2011).2

Fatalism suggests that events are predetermined and inevitable, regardless of human actions. It often implies a sense of resignation to fate, where individuals believe that they cannot change the outcome of events.

Later doctrines of fatalism may be described loosely as synonymous with determinism, but it is useful to make a distinction. Whereas determinism can be represented as compatible with moral responsibility, fatalism properly understood would reduce practical ethics to nothing but the advice that humans should resign themselves indifferently to the course of events. Strict fatalism, therefore, is not to be sought in the major Christian controversies arising from differences between Augustinian and Pelagian, semi-Pelagian, or Molinist doctrine on free will, on grace, and on predestination. Among Christians, the Quietists, with their uncritical reliance on inspiration, may be regarded as having approached more closely to the fatalistic norm of behaviour than any of the commonly recognized partisans of determinism, such as Calvinists or Jansenists (Britannica, 2017, para. 2).

1. Dr. John C. Polkinghorne (Prof, Mathematical Physics at Cambridge; PhD, Quantum Field Theory at Cambridge; PhD, Theoretical Elementary Particle Physics from Trinity College)

2. Dr. Michio Kaku (PhD, University of California, Berkeley).

1.1 Double Predestination

- 🔴 “The dreadful error of hyper-Calvinism is that it involves God in coercing sin. This does radical violence to the integrity of God’s character” (Sproul, 1986, Ch. 7).1

Individuals who embrace the doctrine of double predestination, which is the most deterministic soteriology, hold an unyielding and chilling view of divine sovereignty. This doctrine asserts that God, in His absolute authority, has predetermined the fate of every individual—determining their election to salvation and their reprobation to eternal damnation, all before they even draw their first breath. In this harrowing soteriology, the vessels of wrath and the vessels of mercy (Rom. 9:22-23) are fixed and irrevocably established… even before the very foundations of the earth were laid.

Chapter III.

Of God’s Eternal DecreeIII. By the decree of God, for the manifestation of His glory, some men and angels6 are predestinated unto everlasting life; and others foreordained to everlasting death.7

61Ti 5:21; Mat 25:41

7Rom 9:22,23; Eph 1:5,6; Pro 16:4…

VII. The rest of mankind God was pleased, according to the unsearchable counsel of His own will, whereby He extends or withholds mercy, as He pleases, for the glory of His sovereign power over His creatures, to pass by; and to ordain them to dishonor and wrath for their sin, to the praise of His glorious justice.17

17Mat 11:25,26; Rom 9:17,18,21,22; 2Ti 2:19,20; Jd 4 NET; 1Pe 2:8

(Westminster Confession of Faith, 1647/2021, pp. 27-30).

For those marked as vessels of wrath, the chilling truth is that their eternity in hell—engulfed in flames and unending torment—was preordained by God before their existence. This fate is not a mere consequence of their actions; it is a divine decree, a grim reality that magnifies God’s glory in the most unsettling and terrifying way imaginable.

The dreadful error of hyper-Calvinism is that it involves God in coercing sin. This does radical violence to the integrity of God’s character (Sproul, 1986, Ch. 7).1

I cannot imagine a more ready instrument in the hands of Satan for the ruin of souls than a minister who tells sinners it is not their duty to repent of their sins [and] who has the arrogance to call himself a gospel minister, while he teaches that God hates some men infinitely and unchangeably for no reason whatever but simply because he chooses to do so. O my brethren! may the Lord save you from the charmer, and keep you ever deaf to the voice of error. — In Murray, Spurgeon v. Hyper-Calvinism, 155–56.

3. Universal, divine, determinism makes God the author of sin and precludes human responsibility. In contrast to the Molinist view, on the deterministic view even the movement of the human will is caused by God. God moves people to choose evil, and they cannot do otherwise. God determines their choices and makes them do wrong. If it is evil to make another person do wrong, then on this view God is not only the cause of sin and evil, but becomes evil Himself, which is absurd. By the same token, all human responsibility for sin has been removed. For our choices are not really up to us: God causes us to make them. We cannot be responsible for our actions, for nothing we think or do is up to us (Craig, 2010, “Five difficulties” section).2

… In light of this, the use of this text to promote “double predestination” seems completely wrong (Lennox, 2018, p. 246).3

There are some who take these texts to mean that in eternity God mysteriously or even arbitrarily chose who was to be a vessel of wrath and who was to be a vessel of mercy; and that choice permanently and unconditionally fixes their destinies. There is a fundamental flaw in this reasoning, even apart from the fact that it makes no moral sense. The flaw is to assume that, if someone is a vessel of wrath, they can never become a vessel of mercy. But that is false, as Jeremiah’s use of the potter analogy indicates. Paul was a vessel of wrath who became a vessel of mercy. Also, in Ephesians, Paul describes the believers as having once been children of wrath, but because they had repented and trusted Christ as Saviour and Lord they had become vessels of mercy (see Ephesians 2:3–4) (Lennox, 2018, p. 272).3

1. Dr. R. C. Sproul (PhD, Whitefield Theological Seminary)

2. Dr. William Lane Craig (PhD, University of Birmingham; ThD, University of Munich)

3. Dr. John C. Lennox (PhD, Mathematics at the University of Cambridge)

II. ⛓️ Soft-Determinism

2.1 Unconditional Single Election & Freedom of Inclination

- 🟡 This does not involve God in coercing sin. This is the only deterministic option that is possible.

The concept of freedom of inclination permits individuals to act freely only within the confines of their depravity; without divine election and regeneration, the unregenerate are unable to choose salvation and are consequently called slaves of depravity. This viewpoint remains fundamentally deterministic, because this is a death sentence for the unelect. Hopefully, you win the election lottery.

Volitionally the unconverted consistently exercise their wills against God and his purposes. Peter wrote that reprobates promise the unwary freedom, “while they themselves are slaves of depravity—for a man is a slave to whatever has mastered him” (2 Pet 2:19) (Demarest, 2006, p. 74).1

This notion is reminiscent of and echoes Aristotle’s beliefs, as articulated in Book III of the Nicomachean Ethics, as cited by Singer and Eddon (2022) in their article on the Encyclopedia Britannica:

Aristotle (384–322 bce) wrote that humans are responsible for the actions they freely choose to do—i.e., for their voluntary actions. While acknowledging that “our dispositions are not voluntary in the same sense that our actions are,” Aristotle believed that humans have free will because they are free to choose their actions within the confines of their natures. In other words, humans are free to choose between the (limited) alternatives presented to them by their dispositions (para. 2).

Demarest (2006) articulates this asymmetrical view effectively:

The Roman and Arminian views posit sinful men and women as the ultimate determiners of their own salvation, whereas Augustinians and Reformed identify God as the ultimate and efficient cause of eternal blessedness. According to the former traditions, the distinction between the saved and the unsaved is grounded in the choice of the creature; according to the latter, the distinction is grounded in the good pleasure and will of God, however unclear the rationale thereof may be to us mortals. The weight of biblical and historical evidence rests in favor of a single unconditional election to life. This position holds that out of the mass of fallen and responsible humanity—for reasons known to himself—God in grace chose some to be saved and to permit the others to persist in their sin. Against the symmetrical view of Romanists and Arminians (double foreknowledge) and Hyper-Calvinists and Barthians (double predestination), the biblical evidence leads us to posit an asymmetrical view of soteriological purpose—namely, unconditional election to life and conditional election to damnation. When we speak about damnation, we mean that God predestines persons not to sin and disobedience but to the condemnation that issues from sin (pp. 137-138).1

1. Dr. Bruce Demarest (PhD, University of Manchester)

III. 🤖 Indeterminism & Libertarianism

- 🟡 “It is a matter for metaphysical decision which of these alternatives is to be chosen, a point made clearly enough by the existence of both an indeterministic interpretation (Niels Bohr) and a deterministic interpretation (David Bohm) of quantum theory, each having the same empirical adequacy in relation to experimental results, so that physics by itself cannot settle the issue between them” (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. xi).1

This view posits that not all events are determined by preceding causes, allowing for randomness or chance. Indeterminism opens the door for a form of free will, as it suggests that some events (including human decisions) can occur without being predetermined. Dr. Michio Kaku, a theoretical physicist and co-founder of string field theory, emphasizes the implications of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle on free will:

… Heisenberg then comes along and proposes the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle and says: “Nonsense. There is uncertainty. You don’t know where the electron is. It could be here, here or many places simultaneously.” This of course Einstein hated because he said God doesn’t play dice with the universe. Well hey, get used to it. Einstein was wrong. God does play dice. Every time we look at an electron it moves. There is uncertainty with regards to the position of the electron.

So what does that mean for free will? It means in some sense we do have some kind of free will. No one can determine your future events given your past history. There is always the wildcard. There is always the possibility of uncertainty in whatever we do.

So when I look at myself in a mirror I say to myself what I’m looking at is not really me. It looks like me, but it’s not really me at all. It’s not me today now. It’s me a billionth of a second ago because it takes a billionth of a second for light to go from me to the mirror and back (Kaku, 2011, 0:42).2

Dr. John C. Polkinghorne, a distinguished professor of Mathematical Physics at Cambridge University, emphasizes in his book Science and Providence:

The twentieth-century discovery of intrinsic unpredictabilities present in physical process, both at the microscopic level of quantum theory and at the macroscopic level of chaos theory, had brought about the demise of a merely mechanical picture of the physical world, whose workings were no longer seen as being wholly tame and controllable. Yet, unpredictability is an epistemological property, concerned with what can or cannot be known, and it carries no logical entailment of a necessary ontological conclusion concerning what is actually the case. Inability to predict might be due either to ignorance of hidden causal detail of a conventional kind, or it might be the sign of a true openness to the operation of new forms of causal principle. It is a matter for metaphysical decision which of these alternatives is to be chosen, a point made clearly enough by the existence of both an indeterministic interpretation (Niels Bohr) and a deterministic interpretation (David Bohm) of quantum theory, each having the same empirical adequacy in relation to experimental results, so that physics by itself cannot settle the issue between them (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. xi).1

I think, from an undue bewitchment by the Newtonian equations from which chaos theory originally sprang. Of course, as they stand, these equations are deterministic in their character, but we know that they are only approximations to reality, since Newtonian thinking is not adequate at the scale of atomic phenomena. Dismissive talk of ‘deterministic chaos’ is, therefore, a highly challengeable metaphysical decision, rather than an established conclusion of physics. It might be thought that understanding could be advanced by a fusion of quantum theory and chaos theory, since the behavior of chaotic systems soon comes ostensibly to depend upon fine detail at a level of accuracy that is rendered inaccessible by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. xii).1

In Chapter Two, Dr. John C. Polkinghorne emphasizes that our understanding of the universe reveals an openness to the future, challenging the constraints of mechanical determinism and suggesting a more dynamic and less machine-like nature of reality:

We now understand that even at those macroscopic levels where classical physics gives an adequate account, there is an openness to the future which relaxes the unrelenting grip of mechanical determinism. The universe may not look like an organism, but it looks even less like a machine (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. 37).1

In Chapter 5, Dr. John C. Polkinghorne addresses the problem of evil, presenting the free-will defense as a response to atheist critiques, emphasizing that the immediate source of suffering lies in the exercise of human will:

Dreadful as the resulting sufferings are, their immediate source is clear. They result from the exercise of human will. Men and women are directly responsible for them. That responsibility may be diffused, for we are all subject to the pressures of society and of our upbringings, but it is primarily located in humanity. The classic answer to the allowed existence of moral evil is the free-will defense— the claim that it is better for God to have created a world of freely choosing beings, with the possibility of their voluntary response to him and to each other, as well as the possibility of sinful selfishness, than to have created a world of blindly obedient automata (Polkinghorne, 2005, p. 76.).1

In Chapter 7, Dr. John C. Polkinghorne explores the nature of time, arguing that while traditional views may suggest time is an illusion in a deterministic universe, modern quantum theory reveals that successive acts of measurement lead to genuinely new states, emphasizing a dynamic understanding of time:

Time does not elapse; the world line is not traversed. It is simply there. Spacetime diagrams are great chunks of frozen history. Not only can God take an atemporal view of such a universe; it is really the only right perspective from which to consider it. Just before his death Einstein wrote the astonishing words: “For us convinced physicists, the distinction between past, present and future is an illusion, though a persistent one.”

Such talk is only possible in a totally deterministic universe, where Laplace’s calculator can retrodict the past and predict the future from the dynamic circumstances of the present, so that effectively the distinction between past, present and future is abolished. There is simply a given spacetime pattern. That world is a world of being, but it is not a world of becoming. Nothing essentially new can ever happen within it. That world is certainly not the world of human experience, where the past is closed and the future is open. Nor is it the world described by modern science.

In his attitude, Einstein was the last of the great ancients rather than the first of the great moderns. It is notorious that he rejected the radical indeterminism of probabilistic quantum theory. He could not stomach a God who played dice. Yet that is the picture of subatomic process to which almost all physicists subscribe today …

Thus quantum theory does not encourage the view that the flux of time is an illusion. Successive acts of measurement bring about genuinely new states of the system (Polkinghorne, 2005, pp. 89-90).1

Dr. Michael S. Heiser, who holds a PhD in Hebrew Bible and Semitic Languages from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, argues that God’s foreknowledge of all possibilities does not necessitate predestination, emphasizing that these concepts are not inextricably linked:

The fact that God knows possibilities, and all possibilities don’t happen. tells you that God’s foreknowledge of those possibilities did not result in the predestination of all those possibilities. foreknowledge and predestination are not inextricably linked, foreknowledge does not necessitate predestination. God knowing all things real and possible actually undermines that idea (Heiser, 2021, 0:48).3

1. Dr. John C. Polkinghorne (Prof, Mathematical Physics at Cambridge; PhD, Quantum Field Theory at Cambridge; PhD, Theoretical Elementary Particle Physics from Trinity College)

2. Dr. Michio Kaku (PhD, University of California, Berkeley)

3. Dr. Michael S. Heiser (PhD, Hebrew Bible and Semitic Languages at the University of Wisconsin-Madison)

3.1 Libertarian Free Will

- 🔴 Discredited by the "intelligibility" objection.

Libertarianism extends this concept to an illogical extreme. For Christians, the difficulty presented by libertarian free will stems from its total disregard for God’s sovereignty and its profound neglect of Scriptural teachings. Libertarianism contradicts Ephesians 1:13-14 by incorrectly asserting that individuals can nullify their own divine seal through the exercise of their free will, that they can essentially snatch themselves from God’s hand (John 10:28-29), and that they somehow have the free will to overpower God himself (Romans 8:38-39).

Libertarianism is vulnerable to what is called the “intelligibility” objection, which points out that people can have no more control over a purely random action than they have over an action that is deterministically inevitable; in neither case does free will enter the picture. Hence, if human actions are indeterministic, free will does not exist (Britannica, 2024, para. 5).

IV. ⚖️ Theological Compatibilism

- 🟢 In complete harmony with Scripture and Physics.

Compatibilism recognizes God’s sovereignty alongside a limited version of free will. Compatibilism argues that determinism (God’s sovereignty) and free will are not mutually exclusive, in other words, they exist at the same time. They redefine free will to fit within a deterministic framework, or in this context, free will is reconceptualized to align with God’s sovereignty. This is where you will find the world’s brightest theologians and biblical language scholars.

I believe that the doctrine of election is absolutely true while at the same time it’s true that human beings have a free will this is an idea known as compatibilism in theological circles (Rhodes, 2016, 1:58).

1. Dr. Ron Rhodes (ThD, Dallas Theological Seminary)

4.1 Double Foreknowledge & Free Will

The double foreknowledge—often referred to as conditional election—espoused by Romanists and Arminians can be interpreted as a variant of Compatibilism, as it posits that God predestines individuals based on His foreknowledge of their foreseen faith, even prior to their existence. The only way to know if you are one of the elect is to come to faith. Dr. Rhodes (2016) articulates their perspective as follows:

Arminians will come in and say that God’s predetermination or election is based on his foreknowledge, in other words, God looks down through the corridors of time and decides who’s going to respond positively to the gospel and then he will elect those individuals to salvation … (2:58).1

Chuck Smith also taught the Wesleyan Foreknowledge view of election.

We believe that God chose the believer before the foundation of the world (Ephesians 1:4-6), and based on His foreknowledge, has predestined the believer to be conformed to the image of His Son (Romans 8:29-30). We believe that God offers salvation to all who will call on His name. Romans 10:13 says, “ For whosoever shall call on the name of the Lord shall be saved.” We also believe that God calls to Himself those who will believe in His Son, Jesus Christ (1 Corinthians 1:9). However, the Bible also teaches that an invitation (or call) is given to all, but only a few accept it. We see this balance throughout scripture. Revelation 22:17 states, “… And whosoever will, let him take the water of life freely.” 1 Peter 1:2 tells us we are, “Elect according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, through sanctification of the Spirit, unto obedience and sprinkling of the blood of Jesus Christ. …” Matthew 22:14 says, “For many are called, but few are chosen (elected).” God clearly does choose, but man must also accept God’s invitation to salvation (Smith, 2001, p. 10).2

1. Dr. Ron Rhodes (ThD, Dallas Theological Seminary)

2. Chuck Smith (BS, Life Pacific College).

4.2 Single Unconditional Election & Free Will

Reformed variants of asymmetrical Compatibilism assert a definitive emphasis on foreordination rather than prescience. They maintain that we possess free will, but rather than associating it with a prescient foreknowledge, they align it with foreordaining foreknowledge (a.k.a. unconditional single election). While supralapsarian high-Calvinists advocate for a symmetrical double foreordination and Arminians support a symmetrical double prescient foreknowledge, this perspective asserts that foreordination applies solely to election, with conditional election pertaining to reprobation, as Demarest (2006) asserts, “unconditional election to life and conditional election to damnation” (p. 138).1 The distinction between this asymmetry and that of infralapsarian orthodox Calvinists lies in the fact that this model contrasts God’s sovereignty with a limited version of free will, rather than with freedom of inclination.

Arminians will come in and say that God’s predetermination or election is based on his foreknowledge, in other words, God looks down through the corridors of time and decides who’s going to respond positively to the gospel and then he will elect those individuals to salvation the problem with that view is that the Bible doesn’t indicate that God just knows things in advance but he actually determines things in advance he determines what will happen (Rhodes, 2016, 2:58).2

If what Carson means is that that John believes in both God’s sovereignty and human responsibility, and that both must be held equally firmly, however paradoxical the resulting tension may appear to us, then that would be fine. However, the term “compatibilism”, as we mentioned earlier, is normally used by philosophers who hold that human freedom and responsibility is compatible with determinism – a very different matter; unless, of course, one interprets sovereignty as determinism (Lennox, 2018, p. 101).3

I wrote an entire book addressing the posed question: Beyond the Cosmos, now in its third edition. … In that book I explain why each of Calvinism, Arminianism, and Traditionalism are inadequate by themselves to address all that the Bible teaches on sotierology and our relationship with Christ. I point out, for example, that the Bible teaches that both divine predetermination and human free will simultaneously operate. I explain why there is no possible resolution of this paradox within the spacetime dimensions of the universe. However, the Bible teaches and the spacetime theorems prove that God created the cosmic spacetime dimensions and in no way is limited by them. I show three different ways how the paradox of divine predetermination and human free will can be resolved in the extra- and trans-dimensional context of God. I also show how several other biblical paradoxes can be resolved from God’s extra-/trans-dimensional perspective (Ross, 2020, para. 2).4

1. Dr. Bruce Demarest (PhD, University of Manchester)

2. Dr. Ron Rhodes (ThD, Dallas Theological Seminary)

3. Dr. John C. Lennox (PhD, Mathematics at the University of Cambridge)

4. Dr. Hugh Ross (PhD, Astrophysicist at the University of Toronto)

V. ⚖️ Conclusion

Both Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle and, potentially, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems indicate that there are inherent limits to what can be known or measured in both physics and mathematics, thereby negating Newtonian determinism. Given that Scripture affirms God’s absolute sovereignty while also holding individuals accountable for their actions, compatibilism emerges as the most logical conclusion.

5.1 On Proginōskō

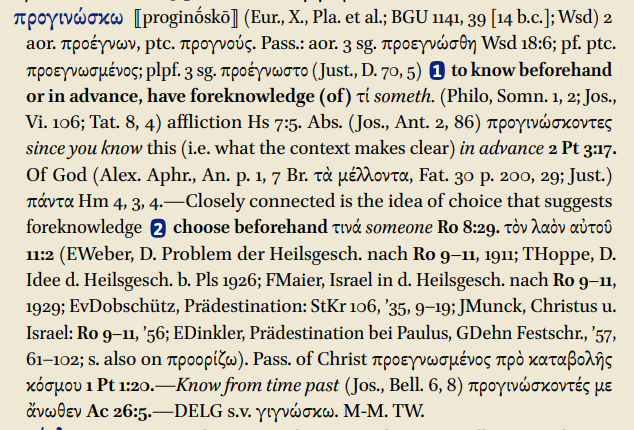

BDAG, the world’s most authoritative Greek lexicon, indicates that the first meaning is applied only to 2 Peter 3:17, whereas the second meaning is applied to Rom. 8:29; Rom. 9-11; 11:2; 1Pet. 1:20; and Acts 26:5.

Demarest (2006) elucidates that the term “foreknew,” rendered as proginōskō in the Golden Chain, can convey two distinct meanings when ascribed to God: it may denote prescience, as interpreted by Arminians, or it may imply foreloving and foreordaining, as understood by Calvinists. He contends:

In Rom 8:28-30 Paul delineated the full circle of salvation, which clinched his argument concerning Christians’ hope of heavenly glory (vv. 18-27).

And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose. For those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the likeness of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those he predestined, he also called; those he called, he also justified; those he justified, he also glorified.

We observe, first, that the foundation of the Christian’s calling to salvation is God’s prothesis, meaning “purpose,” “resolve,” or “decision” (Rom 9:11; Eph 1:11; 3:11; 2 Tim 1:9). The believer’s hope of future glory is grounded not in his own will but in the sovereign, pre-temporal purpose of God.

The first of the aorist verbs in the passage is the word proginōskō, to “foreknow,” “choose beforehand.”111 With humans as subject the word means to “know beforehand” (Acts 26:5; 2 Pet 3:17). With God as subject the verb could mean either prescience or foreloving/foreordaining (Rom 8:29; 11:2; 1 Pet 1:20). The foundational verbs yāda‘ and ginōskō often mean to “perceive,” “understand,” and “know.” But they also mean “to set regard upon, to know with particular interest, delight, affection, and action. (Cf. Gen 18:19; Exod 2:25; Ps 1:6; 144:3; Jer 1:5; Amos 3:2; Hos 13:5; Matt 7:23; 1 Cor 8:3; Gal 4:9; 2 Tim 2:19; 1 John 3:1).”112 The verb ginōskō thus can convey God’s intimate acquaintance with his people, specifically the fact that they are “foreloved” or “chosen.” This latter sense is evident in the following Pauline sayings: “the man who loves God is known by God” (1 Cor 8:3); “but now that you know God—or rather are known by God” (Gal 4:9); and “the Lord knows those that are his” (2 Tim 2:19).

The verb proginōskō in Rom 8:29 and 11:2 contextually could be taken in either of the two senses, i.e., prescience or foreordination. But given the strongly relational Hebrew background to the word, the unambiguous sense of proginōskō in 1 Pet 1:20 (see below) and prognōsis in Acts 2:23 and 1 Pet 1:2 (see below), and the whole tenor of Paul’s theology, the probable meaning of proginōskō with God as subject is to “know intimately” or “forelove.”113 F.F. Bruce concurs with this judgment. Concerning Rom 8:29, he wrote, “the words ‘whom he did foreknow’ have the connotation of electing grace which is frequently implied by the verb ‘to know’ in the Old Testament. When God takes knowledge of his people in this special way, he sets his choice upon them.”114 To the preceding considerations we add that the biblical language of foreknowledge is always used of saints, never of the unsaved. Moreover, what God “foreknows” is the saints themselves, not any decision or action of theirs. Thus divine election is according to foreknowledge (foreloving), not simply according to foresight (prescience) (pp. 127-128).1

1. Dr. Bruce Demarest (PhD, University of Manchester)

5.2 Men as Responsible

Dr. Carson elaborates on the concept of human responsibility in Chapter 3 of his book Divine Sovereignty and Human Responsibility: Biblical Perspectives in Tension. The following are section headings:

Men face a plethora of exhortations and commands; men are said to obey, believe, choose; men sin and rebel; men’s sins are judged by God. Men are not held to be responsible in some merely abstract fashion; they are responsible to someone; men are tested by God; men receive divine rewards; human responsibility may arise out of God’s initiative; the prayers of men are not mere showpieces; and God utters pleas for repentance (Carson, 2002, pp. 18-23).1

1. Dr. D. A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge)

5.3 God as Sovereign

Dr. Carson elaborates on the concept of God’s Sovereignty in Chapter 3 of his book Divine Sovereignty and Human Responsibility: Biblical Perspectives in Tension, stating that:

Chance is excluded; and if here and there we read of something that might be considered a chance event, it is not really thought of apart from God’s direction (1 Sam. 6.9; 20.26; 1 Kgs. 22.34; Ruth 2.3; 2 Chr. 18.33). Hence the lot is used to discover Yahweh’s will, ‘and is didactically recognised as under His control’ (Prov. 16.33; cf. Josh. 7.16; 14.2; 18.6; 1 Sam. 10.19-21; Jonah 1.7) (Carson, 2002, pp. 25-26).1

Human thoughts and decisions are often attributed directly to God’s determining (e.g. 2 Sam. 24.1; Isa. 19.13f.; 37.7; Prov. 21.1; Ezra 1.1; 7.6, 27f.; Neh. 2.11f.) (Carson, 2002, p. 27).1

Examples are so numerous that only a few instances may be cited. Micaiah’s description of the heavenly courts and the selection of a lying spirit whose success is guaranteed (1 Kgs. 22.19-22; 2 Chr. 18.18-22), the inciting of David to evil purpose (2 Sam. 24.1), the selling of Joseph into slavery (Gen. 50.20), the sending forth of evil spirits to their appointed tasks (e.g. Judg. 9.23ff.; 1 Sam. 16.14; 18.10), the prologue of Job, not to mention the specific remarks of the prophets (e.g. Does evil (rā’āh) befall a city, unless the LORD has done it?” Amos 3.6; cf. Isa. 14.24-7; 45.7), all clamour for attention (Carson, 2002, p. 29).1

… God is also said to control the minds of his people for good. Sometimes he is petitioned to do so. Such expressions are particularly common in the prophets who look forward to the new covenant (cf. Jer. 31.31-4; 32.40; Ezek. 11.19f.; 36.22ff.; Zeph. 3.9-13; etc.), but are certainly not restricted to such a framework (e.g. 1 Chr. 29.17-19) (Carson, 2002, p. 29).1

Yahweh is holy, sovereign, full of special regard for his elect, and personally ruling in the affairs of men. This view of God makes the perplexity of his people understandable when, from the human perspective, it appears that Yahweh has dealt harshly (Ruth 1.20f.), unfairly (Job 3ff.), or without due consideration of the wickedness of other men (Habbakuk; Ps. 73). It prompts a cry like that in Isaiah 63.17: ‘O LORD, why dost thou make us err from thy ways, and harden our heart, so that we fear thee not? Return for the sake of thy servants, for the tribes of thy heritage. (Cf. also Isa. 64.7f.) (Carson, 2002, p. 30).1

1. Dr. D. A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge)

5.4 Free will Test

I’d like to start out by asking you a few questions; we’ll call it the free will test, if you will:

- Did you have the free will to choose your birthplace, such as the United States, Canada, China, India, Brazil, Nigeria, or Germany?

- Did you have a choice in being born as a Caucasian (White), African (Black), Asian, Hispanic or Latino, Indigenous Peoples, Pacific Islander, or Middle Eastern?

- Did you have any influence over the socioeconomic conditions into which you would be born?

- Did you choose your relatives, including your grandparents, parents, or siblings?

- Did you have a free will choice over your inherited genetic disorders, like cystic fibrosis, Huntington’s disease, and sickle cell anemia? All are determined by specific genetic mutations that individuals inherit from their parents, and they cannot choose to avoid these conditions.

- Did you have a choice in your physical traits? Characteristics such as eye color, hair color, and height are largely determined by genetics. Individuals have no control over the specific combination of genes they inherit that dictate these traits.

- Do you have a choice in your predisposition to diseases, such as breast cancer (e.g., BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations) or heart disease? These are inherited and cannot be chosen or altered by the individual.

- Did you have a choice regarding your intelligence, knowing that while environmental factors play a role, genetics significantly influence cognitive abilities and intellectual potential?

- Did you have any control over the determination of your aptitudes, including your natural talents and abilities in music, mathematics, sports, and language?

- Do you have a choice over the outcome of randomness, chance, or catastrophe?

- Can you save yourself by reciting a works-based sinner’s prayer or declare yourself justified before God through your own free will choices?

- Finally, do you believe that you have the free will to renounce your faith and forfeit salvation?

5.5 Final Thoughts

In the scriptures, we observe the coexistence and a nuanced interplay between determinism, in the form of God’s sovereignty, and a degree of free will. However, the question arises: do these two concepts exist simultaneously in a state of constant tension? Heiser (2021) argues convincingly against this notion, stating:

The fact that God knows possibilities, and all possibilities don’t happen. tells you that God’s foreknowledge of those possibilities did not result in the predestination of all those possibilities. foreknowledge and predestination are not inextricably linked, foreknowledge does not necessitate predestination. God knowing all things real and possible actually undermines that idea (0:48).3

At the same time, Drs. Carson (2002), Polkinghorne (2005, p. xi), Polkinghorne reluctantly, Ross (2020), and Rhodes (2016) demonstrate the presence of determinism:

Arminians will come in and say that God’s predetermination or election is based on his foreknowledge, in other words, God looks down through the corridors of time and decides who’s going to respond positively to the gospel and then he will elect those individuals to salvation the problem with that view is that the Bible doesn’t indicate that God just knows things in advance but he actually determines things in advance he determines what will happen (Rhodes, 2016, 2:58).5

It’s possible that conditional election is correct regarding salvation, but incorrect concerning other instances where God may have chosen to implement a more deterministic and unconditional framework. If foreknowledge does not necessitate predestination, and if God does not merely possess knowledge of future events but actively determines them, then we must conclude, in accordance with the axiomatic laws of thought—specifically, the law of non-contradiction—that God chooses to exercise His determinative power selectively or in a state of flux, rather than continuously in a constant state.

Concluding remarks: The idea that God really is the sovereign disposer of all is consistently woven into the fabric of the Old Testament, even if there is relatively infrequent explicit reflection on the sovereignty-responsibility tension. Taken as a whole, the all-embracing activity of the sovereign God in the Old Testament must be distinguished from deism, which cuts the world off from him; from cosmic dualism, which divides the control of the world between God and other(s); from determinism, which posits such a direct and rigid control, or such an impersonal one, that human responsibility is destroyed; from indeterminism and chance, which deny either the existence or the rationality of a sovereign God; and from pantheism, which virtually identifies God with the world (Carson, 2002, p. 35).1

1. Dr. D. A. Carson (PhD, University of Cambridge)

2. Dr. John C. Polkinghorne (Prof, Mathematical Physics at Cambridge; PhD, Quantum Field Theory at Cambridge; PhD, Theoretical Elementary Particle Physics from Trinity College)

3. Dr. Michael S. Heiser (PhD, Hebrew Bible and Semitic Languages at the University of Wisconsin-Madison)

4. Dr. Hugh Ross (PhD, Astrophysicist at the University of Toronto)

5. Dr. Ron Rhodes (ThD, Dallas Theological Seminary)

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2017, August 31). Fatalism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/fatalism

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2024, November 15). Free will. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/free-will

- Carson, D. A. (2002). Divine sovereignty and human responsibility: Biblical perspectives in tension. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Craig, W. L. (2010, April 19). #157 Molinism vs. Calvinism. Reasonable Faith. https://www.reasonablefaith.org/writings/question-answer/molinism-vs.-calvinism

- Demarest, B. (2006). The cross and salvation. Crossway Books.

- ESV Study Bible (ESV Text Edition: 2016). (2008). Crossway.

- Heiser, M. S. (2021, July 6). Does Foreknowledge require Predestination? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/kwyZxAtTHfc&t=48

- Kaku, M. (2011, May 20). Michio Kaku: Why physics ends the free will debate [Video]. Big Think. https://youtu.be/Jint5kjoy6I

- Lennox, J. C. (2018). Determined to believe?: The sovereignty of God, freedom, faith, and human responsibility. Zondervan.

- Martin, W. (2017, Jul 9). The mystery of predestination [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/uuUKE5resPs&t=1225

- Polkinghorne, J. C. (2005). Science and providence: God’s interaction with the world. (Templeton Foundation Press ed.). Templeton Foundation Press.

- Rhodes, R. (2016, Sep 13). The doctrine of election, foreknowledge and freewill [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/pTuY7ZZ_6jk&t=118

- Ross, H. (2017). Beyond the cosmos: The transdimensionality of God (3rd ed.). Reasons to Believe.

- Ross, H. [@RTBHughRoss]. (2020, September 9). Question of the Week: Of the main sotierology models within evangelicalism to which do you adhere: Calvinism, Arminianism, or Traditionalism?. Facebook. https://m.facebook.com/RTBHughRoss/posts/3266294876781927/

- Singer, P. & Eddon, M. (2022, August 3). Free will and moral responsibility. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/free-will-and-moral-responsibility

- Smith, C. (2001). Calvinism, arminianism, & the word of God, a Calvary Chapel perspective. The Word For Today.

- Sproul, R. C. (1986). Chosen by God. Tyndale House Publishers.

- Westminster Confession of Faith. (2021). Versa Press. (Original work published 1647)

Together in action, united in spirit, aligned in purpose. Ordo Dei Invictus.